Joe Mooney Quartet, Tea for Two.

Blossom Dearie, Tea for Two.

Bud Powell, Tea for Two.

Bob Wills, Tea for Two.

Symphony Orchestra of Beijing, Picking Tea Leaves.

Alvin Ing, et al, Chrysanthemum Tea.

Manfred Mann, Trouble and Tea.

The Boswell Sisters, When I Take My Sugar to Tea.

Leon Redbone, When I Take My Sugar to Tea.

The Kinks, Afternoon Tea.

The Kinks, Have a Cuppa Tea.

The Police, Tea in the Sahara.

Shelby Lynne, Iced Tea.

Nirvana, Pennyroyal Tea.

Holy Modal Rounders, Tea Song.

Benny Goodman w/Jack Teagarden, Texas Tea Party.

A Prelude

"Ye Cosy Nooke, as its name will immediately suggest to those who know their London, is a tea-shop in Bond Street, conducted by distressed gentlewomen. In London, when a gentlewoman becomes distressed--which she seems to do on the slightest provocation--she collects about her two or three other distressed gentlewomen, forming a quorum, and starts a tea-shop in the West-End, which she calls Ye Oak Leaf; Ye Olde Willow-Pattern, Ye Linden-Tree, or Ye Snug Harbour, according to personal taste.

There, dressed in Tyrolese, Japanese, Norwegian, or some other exotic costume, she and her associates administer refreshments of an afternoon with a proud languor calculated to knock the nonsense out of the cheeriest customer...They rely for their effect on an insufficiency of light, an almost total lack of ventilation, a property chocolate cake which you are not supposed to cut, and the sad aloofness of their ministering angels. It is to be doubted whether there is anything in the world more damping to the spirit than a London tea-shop of this kind, unless it be another London tea-shop of the same kind.

Maud sat and waited. Somewhere out of sight a kettle bubbled in an undertone, like a whispering pessimist. Across the room two distressed gentlewomen in fancy dress leaned against the wall. They, too, were whispering. Their expressions suggested that they looked on life as low and wished they were well out of it, like the body upstairs. One assumed that there was a body upstairs. One cannot help it at these places. One's first thought on entering is that the lady assistant will approach one and ask in a hushed voice "Tea or chocolate? And would you care to view the remains?"

P.G. Wodehouse, A Damsel In Distress.

Have A Cuppa

Each drink is, in its own way, an embodiment of civilization, but tea drinking is civilization at its most refined and at its most removed--it is serenity in a cup, a few minutes of humbly brewed peace, satori achieved with the union of hot water and tea leaves.

Everything about tea is charged with ritual, from the intricacies of picking tea leaves and flowers to the formalized tea ceremonies of Japan, down to the steps one takes in the kitchen to make tea (waiting for the kettle to boil, steeping the teabag for a specific time). Tea is not to be gulped down but rather mulled over; it is passive.

There are fewer songs about tea than for most other drinks, at least in terms of Western popular music (there are allegedly hundreds of traditional Chinese and Japanese tea songs, hardly any of which I’ve heard). Is it because tea has an effete sensibility? There are few, if any, lusty odes to tea, nor any rowdy ones, and associating tea with rebellion or a wild night out seems ludicrous--rather, tea is part and parcel with the home. Tea songs are meant for quiet afternoons, for pensive hours. It's a private, privileged drink--the singer of "When I Take My Sugar to Tea" is trying to go for a higher-class girl, and so "I never take her where the gang goes". Instead, he's going to tea at the Ritz.

(Two servings of tea with sugar: the glorious Boswell sisters, in a fantastic, fantastic recording from 1931. On Shout Sisters Shout!. And Leon Redbone's version from 1991, on Sugar. The latter courtesy of the Rev. Frost, who has been providing songs for every one of these drinks.)

A confession: I do not really like tea that much, except when I’m sick with a sore throat, so perhaps subconsciously I associate tea drinking with being ill. But more likely, I think that one must at some point in life decide between tea and coffee, and many long years ago I became indentured to coffee. So, through no fault of its own, tea has always seemed to be an inadequate substitute.

The Choice

Coffee and tea represent two different modes of being. In the book The World of Caffeine (which has been an essential resource for this post, as well as for the coffee post), Bennett Alan Weinberg and Bonnie K. Bealer survey the realm: Coffee drinking is associated with gossip, fevered activity, the workplace, public rooms and is often considered an unhealthy vice, while tea "is associated with the feminine and with the drawing room, quiet social interaction...the drink of the elite, the meditative, the temperate and the elderly."

Weinberg and Bealer even offer a chart, "The Duality of Coffee and Tea", and so I've taken their lead (about half the pairs are theirs, the rest mine. Add your own in the comments.)

Coffee v. Tea

Discord v. Harmony

Casual v. Formal

Obvious v. Subtle

The Frontier v. the Kitchen

Diner v. Hotel

Libertarian v. Statist

Fox v. Hedgehog

Mondays v. Sundays

Earthy v. Wispy

Mornings v. Afternoons

Warner Bros. v. Disney

Sam Spade v. Sherlock Holmes

Captain Kirk v. Doctor Who

Bob Dylan v. Nick Drake

Beethoven v. Mozart

Swift v. Woolf

Tea for Two

"Sir Thomas resolutely declined all dinner: he would take nothing, nothing till tea came—-he would rather wait for tea. Still Mrs. Norris was at intervals urging something different; and in the most interesting moment of his passage to England, when the alarm of a French privateer was at the height, she burst through his recital with the proposal of soup. “Sure, my dear Sir Thomas, a basin of soup would be a much better thing for you than tea. Do have a basin of soup.”

Sir Thomas could not be provoked. “Still the same anxiety for everybody’s comfort, my dear Mrs. Norris,” was his answer. “But indeed I would rather have nothing but tea.”

Jane Austen, Mansfield Park.

While there are few tea songs, there is one perennial in the small bunch. "Tea for Two", written for the Broadway show No No Nanette in 1925 by Vincent Youmans (music) and Irving Caesar (lyrics), soon became a jazz standard, mastered by seemingly any musician of note in the following 80 years.

The song came out of desperation--Harry Frazee, the impresario best known for selling Babe Ruth to the Yankees, was trying to rescue his show "No No Nanette", which had flopped miserably in Detroit during its preliminary run. Frazee, by all accounts a drunken brute, demanded that his songwriters come up with show-stoppers to grab the audience's ear, and Youmans and Caesar pounded out "Tea for Two."

Here are a few different brews:

Blossom Dearie's recording, from 1958, is a wistful, dreamy take on the song, sung marvelously. On Once Upon a Summertime.

Probably my favorite version is by the Joe Mooney Quartet, recorded at the tail end of 1946. Mooney's "Tea" is a hipster's reverie, with some funny improvised lyrics at the end about life in the distant year 1983 (when the kids leave home at 3). The Mooney Quartet (Mooney, who sang and played accordion, Andy Fitzgerald (clarinet), Jack Hotop (g) and Gate Frega (b)) played together only from 1945 to 1948. You can find it on Do You Long for Oolong?

In Bud Powell's assault, Bud discards Youmans' melody after the intro, though it turns up, ghost-like, in some of his bass figures. This is take 10, one of three complete takes recorded by Powell in 1950. "'Tea for Two' represents the demonic Powell," as Gary Giddins wrote--the performance is a maelstrom of sound. From the apparently out-of-print? (what gives, Verve?) Genius of Bud Powell.

And Bob Wills' version--well, come on, it's Bob Wills. It smokes. Recorded live (for a radio broadcast) in 1947, on the out-of-print Tiffany Transcriptions No. 7.

Brew of heaven

"The first cup moistens my lips and throat; the second cup breaks my loneliness; the third cup searches my barren entrails but to find therein some thousand volumes of odd ideographs; the fourth cup raises a slight perspiration--all the wrongs of life pass out through my pores; at the fifth cup I am purified; the sixth cup calls me to the realms of the immortals. The seventh cup--ah, but I could take no more!"

Lu Tong, History of Tea.

Shen Nung, the second of the legendary founding emperors of China (2737 BC-2697 BC), who invented the plow and the concept of husbandry, who named the plants and discovered their many curative powers by eating them (until one killed him), also by happenstance discovered tea.

Shen, walking along at the height of a hot day, sat down in the shade of a tea bush and decided to build a fire and boil some water to drink. As Shen cracked off some branches of the nearby bush, a breeze of destiny blew some of the tea leaves into his pot. After drinking from what had become the first teapot in history, Shen felt both refreshed and a bit high.

Once again, the myth falls a bit far from the likely truth. In fact, historians now believe the Chinese did not discover tea at all, but rather learned about it from either denizens of what is now northern India or various aboriginal tribesmen living throughout Southeast Asia, both of whom had long traditions of chewing and brewing tea leaves.

Yet it was China that became tea's homeland. By the time of Lao Tzu (600-517 BC), the founder of Taoism, tea had become an all-purpose drink, a means to improve health, treat guests and inspire thought.

In 780 AD, Chinese tea merchants hired the greatest Taoist poet, Lu Yu, to write a public relations brief on the benefits of tea, which would be like Maxwell House hiring W.B Yeats to tout coffee. Lu's three-volume work, called Ch’a Ching ("c’ha" being the Mandarin word for tea), is an extravagant exploration of tea in all its varieties and forms.

For example, here is Lu Yu on the texture and look of tea:

Tea may shrink and crinkle like a Mongol's boots, or it may look like a dewlap of a wild ox, some sharp, some curling as the eaves of the house. It can look like a mushroom in whirling flight just as clouds do when they flow out from behind a mountain peak.

There were three distinct ages of tea in China– the brick age, when leaves were pounded into a brick-shaped mold which was then either chewed or boiled; the powder age (during the Sung Dynasty, 960-1279), in which tea was crushed to a powder, mixed with hot water and then whipped into a froth (it was an era whose sensibilities were so delicate that female tea pickers had to keep their fingernails a specified length, so that the leaves didn't touch their skin); and then finally the leaf age, in which tea leaves were cured and then steeped in hot water, a method that began during the Ming Dynasty, @1300. It was via this method, the way most of the world enjoys tea today, that the West would discover the joys of tea, when shipments began to Europe during the 17th Century.

"Picking Tea Leaves", a symphonic adaptation of a Chinese folk song, is performed by the Symphony Orchestra of Beijing Conservatory. Recorded in 1997, it can be found on a 12-disc compilation called Chinese Symphonic Century, found here. I found this track on iTunes--I can't vouch for the quality of the rest of the massive compilation, but "Picking Tea Leaves" is gorgeous.

The shine in your Japan, the sparkle of your China

Sometime in the 7th Century, Buddhist monks from China carried tea across the Sea of Japan to the island that would turn tea drinking into the one of the most elaborate rituals ever accomplished by human beings.

Tea, greatly popular with the Japanese people, was also steeped in the vicissitudes of the Japanese shogunate. Oda Nubonaga (1534-82) collected tea sets, haggling to get a prized set the night before his assassination. His successor, Toyotomi Hideyoshi, was an avid tea lover who, during battles, would have his attendants erect a portable teahouse on the battlefield so that he could practice the tea ceremony in view of his opponents, to inspire fear in them. As a sign of the cultural divide between West and East, try to imagine Ulysses Grant or Dwight Eisenhower doing this.

still from Yasujiro Ozu's The Flavor of Green Tea Over Rice.

"Chrysanthemum Tea" is from Harold Prince and Stephen Sondheim's Pacific Overtures, a 1976 musical that is one of the pair's odder works. A dramatization of how American warships in the 1850s forcibly opened Japan to the joys of free trade, it originally was performed by an all-male Asian cast (thus, Alvin Ing plays the Shogun's mother, the primary singer in "Chrysanthemum Tea"). In "Chrysanthemum Tea", the Shogun's mother tries to rouse her son to the danger the American landing party poses for Japan, and when he seems oblivious or indifferent, she puts something deadly in his tea to solve the Shogun's indecision. Original cast recording here.

Another deadly brew: Manfred Mann's "Trouble and Tea", from 1966. On Chapter Two: The Best of the Fontana Years (i.e., the forgotten years between "Do Wah Diddy Diddy" and "Blinded by the Light").

"The Englishman's Proper Element"

"Dr. Daly. (with the tea-pot):

Pain, trouble, and care,

Misery, heart-ache, and worry,

Quick, out of your lair!

Get you all gone in a hurry!

Toil, sorrow, and plot,

Fly away quicker and quicker –

Three spoons to the pot –

That is the brew of your vicar!

Chorus:

None so cunning as he

At brewing a jorum of tea,

Ha! ha! ha! ha!

A pretty stiff jorum of tea."

W.S. Gilbert, The Sorcerer, 1877.

But it is perhaps the British, relative latecomers to tea drinking, who came to symbolize the practice most of all. While almost no one in Britain drank tea in 1700, nearly the entire country was doing so a century later. And by the Victorian era, the average resident of the British Isles (or any servant of the Empire in India, or Burma, or Suez) was drinking so much tea that they likely would have bled oolong.

One factor was that by 1750, the heyday of the coffehouse was over. The thugs, bookies, pimps and other disreputable sorts that had frequented taverns had at last discovered the coffeehouse was where the action was, and so had migrated. Coffeehouses, rather than being salons of the Age of Reason, had become shady, disreputable hovels.

And certainly no place for women. But something else was. In 1717, a coffehouse proprietor named Thomas Twining opened a store designed to specifically sell tea, especially to women. Ladies could now go to a clean, respectable store and sip tea, or have their servants pick up tea there. By the 1730s, the first tea gardens (a British attempt to ape the Japanese custom) had opened; two decades later, foreigners noticed that even maidservants were drinking the stuff.

For one thing, tea was cheap, even for a wage slave in 18th Century London. And increasingly fashionable, especially when the Duchess of Bedford (according to legend or history), feeling hungry and slothful around four in the afternoon, created the concept of having afternoon tea in the 1840s.

The two paintings above are by Mary Cassatt, and show how ingrained and ritualized tea drinking had become by the end of the 19th Century. From the grand tea gardens of Vauxhall to the working class tea break, tea drinking had come to define an entire people's sensibilities.

"And all these meet at levees;—

Dinners convivial and political;—

Suppers of epic poets;—teas,

Where small talk dies in agonies"

Percy Bysshe Shelley, Peter Bell the Third.

The Kinks, perhaps the most English of English bands, have two tea songs in their catalog. "Afternoon Tea" is sweet and wistful, almost dainty. From 1967's essential Something Else. And "Have a Cuppa Tea", from 1971's Muswell Hillbillies, is half Methodist sermon, half medicine show.

The Open Door

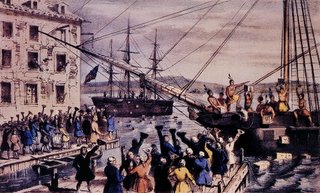

The need to secure a constant, cheap supply of tea, without incurring a massive trade deficit, became one of the ongoing goals of the UK government, leading to such measures as converting India (a country completely ruled by the UK by the 1860s) into the world's leading tea producer and such missteps as imposing the Tea Act in the American colonies, leading to the Boston Tea Party, the American Revolution (and, arguably, a change in American tastes to favor coffee over tea).

China got the worst of it. The problem was that the Chinese were not interested in trading tea for European goods, leading to massive trade imbalances. As the Mekons put it:

The English love for China tea

brought deficit to the economy.

What could we sell back?

Send in the army to deal some smack.

As Tom Standage writes, "an enormous semi-official drug-smuggling operation was established in order to improve Britain's unfavorable balance of payments with China." The drug was opium, grown in Bengal and shipped into China via Canton. And when the Chinese at last attempted to stop the practice, the result was the Opium War (1839-42), which completely shattered and humiliated China, left the country open to a century of Western, Russian and Japanese exploitations, and gave the British Hong Kong.

A late imperial take on tea is the Police's "Tea in the Sahara," on 1983's Synchronicity.

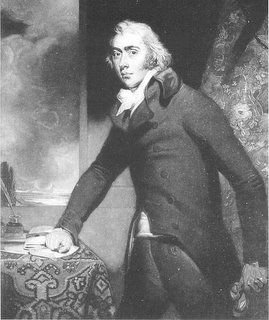

Lord Earl Grey poses for his encyclopaedia picture

Teatime

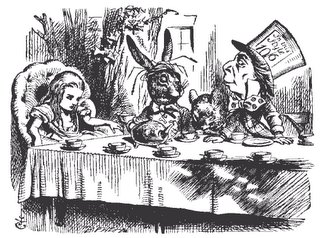

"There was a table set out under a tree in front of the house, and the March Hare and the Hatter were having tea at it: a Dormouse was sitting between them, fast asleep, and the other two were using it as a cushion, resting their elbows on it, and the talking over its head. `Very uncomfortable for the Dormouse,' thought Alice; `only, as it's asleep, I suppose it doesn't mind.'

The table was a large one, but the three were all crowded together at one corner of it: `No room! No room!' they cried out when they saw Alice coming. `There's plenty of room!' said Alice indignantly, and she sat down in a large arm-chair at one end of the table.

`Have some wine,' the March Hare said in an encouraging tone.

Alice looked all round the table, but there was nothing on it but tea. `I don't see any wine,' she remarked.

`There isn't any,' said the March Hare.

`Then it wasn't very civil of you to offer it,' said Alice angrily.

`It wasn't very civil of you to sit down without being invited,' said the March Hare.

`I didn't know it was your table,' said Alice; `it's laid for a great many more than three.'

`Your hair wants cutting,' said the Hatter. He had been looking at Alice for some time with great curiosity, and this was his first speech.

Lewis Carroll, Alice's Adventures in Wonderland.

Before leaving London in the late 1990s, we decided to attempt a true afternoon tea. We picked what seemed an ideal place: a down-on-its-heels establishment in Bloomsbury that several tourist guides had credited for its classic Edwardian tea service.

We showed up at four, entered a stifling drawing room and sat in chairs whose cushions had been shaped to the contours of persons likely long dead, and after a twenty-minute wait were served tea and an assortment of small cakes, which upon contact with the tongue transformed into a thick, chalky paste, biscuits that seemed to have survived the Great War, and spongy cucumber sandwiches.

And then immediately upon our first sip of tea, a trio of dissolute people entered the tearoom. Two of them, who turned out to be Americans, had been drubbed into silence by a combination of jet lag and colossal drug use, and were being led, shuffling and bobbing like marionettes, to a couch nearby by their guide, a British man wearing sunglasses and a leather jacket.

"You're so funny," he told one of his friends, who looked like a stand-in for Lenny Kravitz, only without the money. Then he got on his cel and began telling some other poor soul about his friends. "They've just come from El Lay...yes, oh they're so funny. You're going to love them."

He appeared to be a man who could not bear to entertain a thought, so, after watching his friends sit comatose on the couch for a second, he took a long, commanding look at the drawing room. "This is about as exciting as watching paint peel, isn’t it. Like watching paint peel. I feel like a cadaver. A cah-dahhhhhhh-veh."

It all went to smash after that. The guy kept talking, louder and louder; one of his friends, at last roused to consciousness by his voice, stumbled off to the bathroom and nearly took out a tea table; our tea left a filmy aftertaste that remained for hours afterward; and last we got out after nearly tripping the waiter to get our check. Thus ended my tryst with tradition.

Varieties

Unlike many drinks, tea has not changed much over the years, so a cup of Earl Grey tea today likely tastes similar to how it did in 1850. Standage writes that green tea was the first type of tea to reach European shores, but in the 18th Century, black tea (oolong) became far more popular. For the working class, cheaper varieties of tea were barely tea at all, but tea leaves mixed with all sorts of dicey substances.

Nirvana's "Pennyroyal Tea" is from 1993's In Utero. Pennyroyal tea, which is made from the pennyroyal herb that grows wild in Appalachia, has long been touted for its medicinal properties, but the late Kurt Cobain was referring to the tea's storied use as an abortifacient.

And Shelby Lynne's "Iced Tea" is from Suit Yourself, a record issued this year that was ignored by virtually everyone.

And it's no coincidence that tea has long been aligned with marijuana, whether serving as one of pot's many pseudonyms, or being used as a method of consuming it--the substances look pretty similar in leaf form, and a meditative tea drinking ceremony and sharing a good joint share more qualities than some might like to admit.

The Holy Modal Rounders' take on Michael Hurley's "Tea Song" is described by one of the Rounders, the inimitable Peter Stampfel, like so:

"the song is imbued with some kinda powerful mojo that just won't quit. Notice the chords--it's almost the classic rock & roll 4-chord progression--C/A minor/F/G. Only the last two chords are reversed--C/A minor/G/F. I've never seen another song that uses that haunting and obvious progression. Why not? Only the Shadow knows! Bwa-ha-ha-ha-hah!"

It's on 1999's Too Much Fun.

And go out with the swinging "Texas Tea Party", performed by Benny Goodman's band and sung by the mighty Jack Teagarden, who's wondering where his woman hid the reefer. From 1933, and found on Father of the Jazz Trombone.

Almost done with this never-ending series. One more oversized post, and then a much shorter epilogue. Happy New Year!

No comments:

Post a Comment