Peggy Lee, I Don't Want to Play in Your Yard.

Peggy Lee, A Brown Bird Singing.

Frank Sinatra, In the Wee Small Hours of the Morning.

Frank Sinatra, I'll Be Around.

How distant the war years had become: the gulf between the hot, sparkling summer of 1955 and the grim one of 1942, the summer of Guadalcanal and Stalingrad, must have seemed colossal, as though the entire world had undergone such a sea change that you were surprised, upon finding a wartime newspaper, that the people alive then had spoken the same language as you. Figures from that time who still held the stage--a Churchill or DeGaulle--seemed as fantastics, waxworks breathed into frail life.

In 1955, Frank Sinatra turned 40, and Peggy Lee was 35. Could they even recall those days--the long nights on the bandstand (Sinatra with Tommy Dorsey, Lee with Benny Goodman) waiting for their cues? The overcrowded, stifling USO dances; the smell of Vitalis and Lucky Strikes; the girls clinging to boyfriends or husbands about to be shipped off to die in Anzio or Normandy; the buses hauling the musicians across the night, to Dubuque and Cheyenne and Sioux City; grabbing meals at the automat, washing clothes in a hotel sink. Sinatra causing girls to scream in waves when he sang; Lee terrified in the spotlight, feeling like a hayseed from North Dakota, being forced to wear the same gowns as Helen Forrest, the singer she was replacing.

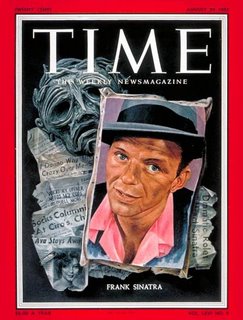

But the world had turned, and Sinatra, in particular, had had a hard time of it. By the late '40s, his singles were flopping; it seemed he couldn't find good material if he paid for it, and once on stage at the Copacabana his voice simply died. He grew a moustache that made him look like a car salesman and hosted an ill-fated television show. Most of all, his romance with Ava Gardner, likely the love of his life, withered and died, all in front of the eager public, who voraciously followed the marriage's collapse via gossip columns and magazines.

Lee tumbled as well. She had married her guitarist, David Barbour, and for a while carried off a life tailored for the celebrity press--the happy Lee/Barbour family, raising a daughter, composing songs, vacationing in Mexico. But Barbour was an alcoholic who at one point allegedly sold off the rights to one of their compositions, "Manana", for two tickets to the Rose Bowl.

Lee recovered first. She divorced Barbour in '51, and, with a child to support, began to reinvent herself for the new decade. She signed with Decca after Capitol had rejected her and Gordon Jenkins' interpretation of "Lover," which turned the Rodgers and Hart number into a wild, almost surreal whirlwind of sound. At Decca, she crafted far more sultry, jazz-infused and intelligent music than she had during her early Capitol years--songs like "Black Coffee", "My Heart Belongs to Daddy", "There's a Small Hotel."

Sinatra caught some breaks too--he landed the role he craved in '53's From Here to Eternity (a process referred to not-so-obliquely in The Godfather, though I don't think Buddy Adler got a horse's head in his bed), which made him legitimate again, and helped him land a new contract with Capitol.

And Sinatra was one of the first of the swing-era musicians to grasp the realities of the new world--people were living in the suburbs, they had kids, and the domestic sphere had begun to encompass all. Why haul the family to the movies when you had TV? Why go downtown, to increasingly shady nightclubs and decaying parking lots, when you could just go to the store and buy a new 12" LP? So Sinatra and his arrangers began crafting concept records--song suites meant to serve as a sonic backdrop to home life, to a dinner party, for a drunken, lonely evening.

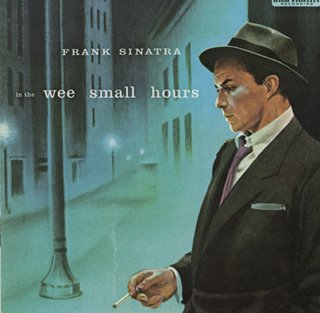

In the Wee Small Hours was Sinatra's first full-length LP to follow this formula, and the mood conveyed was melancholy, loss and regret. Sinatra created the persona--one depicted on the LP's cover: a stoic, wistful Frank, standing alone in a blue mist, with just a cigarette for company. It's a musical take on film noir, with Sinatra playing Philip Marlowe, and Nelson Riddle's arrangements for the LP follow the same cue: many of them could have easily served as scores for Force of Evil or The Postman Always Rings Twice (the sudden swings of the orchestra in "Last Night When We Were Young," the ominous introduction to "Deep in a Dream").

Here are two tracks from the album--the classic title song, written by David Mann and Bob Hilliard (one of the few newly-composed songs on the LP), was recorded on February 17, 1955, while Alec Wilder's "I'll Be Around", recorded on Feb. 8, has one of Sinatra's most compelling vocals--completely humble, supplicating his estranged lover with words infused with desperate hope.

Wee Small Hours is one of those essential records that seemingly everyone recommends, but really, it's that good.

Lee followed a similar path (Black Coffee is another early "concept" LP, and Lee found success in films as well) but she took an interesting turn in 1955. She had found a book of Chinese poems that captivated her, and intrigued, she set about adapting poems like Tu Fu's "Going Rowing" and Li Po's "The Fisherman" to song, using just harpsichord and harp as accompaniment.

Unlike Wee Small Hours, Sea Shells reached no one, because Decca put the LP on ice, finding the whole concept indulgent and bizarre (this seems in retrospect a bone-headed move, as Decca was ignoring the growing popularity of "Far East" sounds, like Martin Denny's records--you'd have thought South Pacific's massive success would have rung a bell somewhere). Finally, they released it in 1958 to massive indifference.

It's a shame, as Sea Shells is a rare thing of quiet beauty. I wouldn't call it Lee's best work--it's just too odd in places, and Lee is pushing so hard for something outside her usual sphere that at times she strains. But much of the record is astonishing: "I Don't to Play in Your Yard" and "Brown Bird Singing" are among the most exquisite songs Lee ever performed--her vocal on each is crystalline, expertly sung and phrased.

"I Don't Want to Play in Your Yard" is the refrain of an 1894 ballad by Phillip Wingate and H.W. Petrie. It was a popular song throughout the early 20th Century, (sometimes rewritten as "Playmate") sung in school plays, and memorized by generations of kids (including Peggy, most likely). "Brown Bird Singing," by Royden Barrie (a pseudonym for Rodney Richard Bennett, father of Richard Rodney Bennett) and Haydn Wood, hails from 1922.

Both were recorded on February 7, 1955, and released three years later on Sea Shells, Decca DL 8591. Lee sings, and Stella Castellucci is on harp (Castellucci wound up getting co-credit on the original Decca LP). The best place to find it is either on a Japanese import or on a 2-fer CD with Black Coffee (a fine record in its own right).

No comments:

Post a Comment