Australian soldier with wounded comrade, Gallipoli.

Peerless Quartet, Alagazam (To the Music of the Band).

Lionel Belasco, Bajan Girl.

Ernest Farrar, English Pastoral Impressions: Over the Hills and Far Away.

Alfred Lester, A Concientious Objector.

Sam Mayo, Bread and Marmalade.

John Young and Frederick Wheeler, When The Roll Is Called Up Yonder.

Claude Debussy, Sonata For Flute, Viola and Harp: Pastorale.

I HAVE BEEN FIGHTING FOR TWO MONTHS and I can now gauge the intensity of life.

HUMAN MASSES teem and move, are destroyed and crop up again.

HORSES are worn out in three weeks, die by the roadside.

DOGS wander, are destroyed, and others come along.

WITH ALL THE DESTRUCTION that works around us NOTHING IS CHANGED, EVEN SUPERFICIALLY. LIFE IS THE SAME STRENGTH. THE MOVING AGENT THAT PERMITS THE SMALL INDIVIDUAL TO ASSERT HIMSELF.

THE BURSTING SHELLS, the volleys, wire entanglements, projectors, motors, the chaos of battle DO NOT ALTER IN THE LEAST, the outlines of the hill we are besieging. A company of PARTRIDGES scuttle along before our very trench.

IT WOULD BE FOLLY TO SEEK ARTISTIC EMOTIONS AMID THESE LITTLE WORKS OF OURS...

THIS WAR IS A GREAT REMEDY.

IN THE INDIVIDUAL IT KILLS ARROGANCE, SELF-ESTEEM, PRIDE.

MY VIEWS ON SCULPTURE REMAIN ABSOLUTELY THE SAME.

IT IS THE VORTEX OF WILL, OF DECISION, THAT BEGINS.

I SHALL DERIVE MY EMOTIONS SOLELY FROM THE ARRANGEMENT OF SURFACES, I shall present my emotions by the ARRANGEMENT OF MY SURFACES, THE PLANES AND LINES BY WHICH THEY ARE DEFINED.

Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, letter to Wyndham Lewis, 1915, written shortly before Gaudier-Brzeska was killed on a charge at Neuville St. Vaast, on 5 June 1915. Reprinted in Blast, July 1915.

Strand, Wall Street.

The Peerless Quartet was a studio supergroup, something like the Asia of the cylinder era. Founded by the bass singer Frank C. Stanley, the quartet's members included Henry Burr, Steve Porter, Albert Campbell and Arthur Collins. They were originally known as the Columbia Quartet until, although still recording for Columbia, they changed their name to "Peerless" (a name allegedly nicked from an African-American quartet of the late 19th C) around 1912.

The group in its various incarnations made thousands of records for a variety of labels, until it finally disbanded in 1928, with Burr its only remaining original member.

"Alagazam," written by Andrew Sterling and Harry Von Tilzer, is a lampoon about a "coffee colored" regiment, complete with all the expected Samboisms: the song's all-black regiment is a goon squad that can't shoot straight, and, one sadly assumes, would run away from the front lines flapping their arms and shouting "lawsy!" A few years after it was released, the "Harlem Hellfighters," an all-black infantry regiment (whose members included Bill "Bojangles" Robinson and James Reese Europe) fought with valor in the last months of WWI. They had to fight under French command, though.

Recorded in Camden, NJ, on 25 October 1915 and released as Victor 17904 c/w "When Old Bill Bailey Plays the Ukalele".

Boccioni, Charge of the Lancers.

28 January 1915: Time drags in the trenches. We lie pressed against each other like pigs. Dirty, soiled, unwashed, we stink like old men. There is nowhere to have a shave or a haircut. I hang my black watch on the wall and we sit staring at it.

11 April: I go with my mate Kozhukhin to get our pictures taken. Dear God. I look like an old man in the photo. I don't recognize myself at all. How quickly war can ruin a man...I don't want to look like this. I worry that I shouldn't send this photo to Nyura [his wife]. It is bound to upset my sweet lady. She is still young, she still likes the look of a healthy young man, she wants to still fancy me.

18 April: We take the binoculars and watch the enemy. Visibility is amazing today, everything is crystal clear. The Germans are putting their trench in order, and we can see them taking their mess tins to fetch water...This is our enemy! They look like good, normal people, they all want to live and yet here we are, gathered together to take each other's lives away.

Diary of Vasily Mishnin, Russian soldier, on the Eastern Front, north of Warsaw.

Canadian Armed Forces recruitment poster, designed for the Québécois

Lionel Belasco, born in Barbados and raised in Trinidad, followed the now-established pattern of training as a classical pianist and working in ragtime and dance music. After making some initial records in Trinidad, Belasco moved to New York around 1915, and lived there for the rest of his life.

Belasco is considered a pioneer of calypso, though it would be fairer to say he was the first, most adept popularizer of the music. His "Bajan Girl" is a quiet, lovely piece, suggesting ragtime elevated to the concert hall.

Recorded 7 September 1915 and released as Victor 67674 c/w "My Little Man's Gone Down to Maine" (it was the third time Belasco had cut "Bajan Girl" for Victor--for whatever reason, they rejected two takes he made in August 1915).

"Elinor Blevins, Auto Fiend," ca. 1915-1916 (Shorpy).

22nd November: Daydream about a happy family and nice kids. Will I live to see the day when I have some? I know I should be infinitely grateful for what I do have, but why have I not, to this day, been able to find real happiness, the kind that sets the heart free and brings comfort to the soul? Dear God! Will you ever grant such things to be my lot in life?...What is in store for us? Whatever happens, we will get used to it. If we had to die twice, we would get used to that too.

24th November: When I finally reach our trenches I find a large pool of blood. It has coagulated and turned black. Bits of brain, bone and flesh are mixed in with it. Shell fragments are scattered around. The trail of blood leads to the front of my dugout.

27th November: We find Agati (a fellow officer) distraught. Even though he prodded his men with bayonets, some of them refused to leave the trench and started crying like women. Those who did go suffered heavy casualties from the enemy fire and shells. The entire unit is demoralized.

Diary of 2nd Lt. Mehmed Fasih, officer in the 47th Regiment of the Ottoman Empire, fighting at Gallipoli.

Soon after Ernest Farrar composed his English Pastoral Impressions, op. 26, he enlisted in the Grenadier Guards, and was eventually commissioned as Second Lieutenant, 3rd Battalion Devonshire Regiment. He was killed on a foggy morning about two months before the armistice in 1918, at the battle of Épehy Ronssoy.

Imagine if there had been a global war in the mid-'60s in which John Lennon, Jean-Luc Godard, Smokey Robinson, Philip Roth, Steve Reich, Thomas Pynchon, Daniel Barenboim, Joseph Brodsky, George Clinton, Werner Herzog, James Rosenquist, Wayne Shorter, and Krystof Penderecki were all killed. Something akin to this hypothetical slaughter actually happened in WWI.

All that remains are the great silences, the imagined outlines of the works never made: the stories, poems and novels never written by Trakl, Saki, Alain-Fournier, Apollinaire, Owen, Sorely, Rosenberg; the music not composed by Magnard or Granados or Butterworth; the unmade paintings, buildings and sculptures of Sant'Elia, Marc, Gaudier-Brzeska, Macke, Boccioni. Or the thousands of others who never even got started.

Here is the final movement of Farrar's Pastoral Impressions, "Over the Hills and Far Away." As Paul Fussell wrote in The Great War and Modern Memory, the idea of the pastoral, seen as a lost world forever severed from reality by the war, is infused in the writing of many British soldiers during WWI, from Guy Chapman's "hedges of wire" on the front to Stephen Hewitt, quoting Milton's "tomorrow to fresh woods, and pastures new" in reference to his return to the trenches.

Performed by the Philharmonia Orchestra, conducted by Alasdair Mitchell; find here.

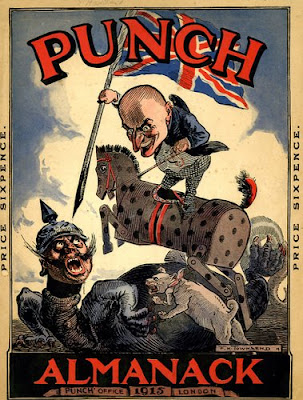

Fussell's book (which you should read) also delves into the surreal English homefront experience, in which the British soldier, after a stretch of death-and-mud-filled months on the front, would ship back across the Channel to go on leave, returning home to a country that seemed nearly untouched by the war, and reading in the papers that he was winning glorious victory after victory and had the Huns on the run. The '70s TV series Upstairs, Downstairs captures this: the randy footman, Edward, comes home from the war a glassy-eyed, timid shellshock, and the haughty, upper-crust James Bellamy becomes a cynical, chain-smoking wraith.

The wartime reporter Philip Gibbs later recounted how many British soldiers came to despise civilians: "They hated the smiling women in the streets. They loathed the old men...they prayed God to get the Germans to send Zeppelins to England--to make the people know what war meant." Siegfried Sassoon, in "Blighters," fantasizes about a group of happy patriotic civilians at a music hall getting mowed down by a tank, and in "Fight to a Finish," imagines returning veterans bayonetting journalists to death in the streets.

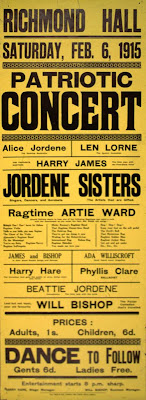

Here are two songs a soldier on leave in London, in 1915, may have heard: Alfred Lester's "A Concientious Objector" ("I don't object to fighting Huns/but should hate them fighting me") and Sam Mayo's "Bread and Marmalade," in which Mayo delivers a wonderfully drunken vocal.

Lester's "Objector" can be found in this archive and Mayo's "Marmalade" was released on 9 January 1915 as Zonophone 2222; find on A Night at the Music Hall.

25 April 1915 [the Gallipoli landing]: Lord, what a day...A galling fire rained on us from the left where there were high cliffs. One man dropped down alongside me laughing. I broke the news to him gently: "you've got yourself into the hottest corner you'll ever strike." I had shown him where the enemy were, he fired a few shots. And again I heard the sickening thud of a bullet. I look at him in horror. The bullet had fearfully mashed his face and gone down his throat, rendering him dumb. But his eyes were dreadful to behold. How he squirmed in agony. There was nothing I could do for him, but pray that he might die swiftly. It took him about twenty minutes...I saw the waxy colour creep over his cheek and breathed freer.

19 May: Every bush seemed to hide a Turk. Suddenly from the gulley 150 yards from in the front came clear and distinct "Allah!"And at the same second I caught a flicker of a bayonet in the scrub not far ahead. It was a massacre. In half an hour it was over...A wounded Turk told us they regard Australians as fiends incarnate. The Germans told them we were an undisciplined rabble, armed mostly with sticks, axes, etc. But he reckoned we were a lot of mad devils when it came to the bayonet.

Diary of Corporal George Mitchell, Australia, member of the Allied Mediterranean Expeditionary Force, fighting in Gallipoli.

Kirchner, Self-Portrait as a German Officer.

"When the Roll Is Called Up Yonder" was written by James M. Black, a Williamsport, Penn., singing school teacher and an editor of gospel songbooks; it first appeared in Black's 1894 Songs of the Soul, which sold more than 400,000 copies. Black's inspiration came after he called roll at a Sunday school consecration meeting and found that one girl, in his words "poorly clad and the child of a drunkard," wasn't there. This led to Black pondering aloud how woeful it would be at the Resurrection, if the Lord called your name and you were absent. To complete the grim anecdote, the poor girl in question soon caught pneumonia and died.

In 1913, in response to a request to use his song in a hymnal, Black wrote: "Everyone else is raising the prices of the great songs and why should not I? It is the common consent that "When the Roll is Called Up Yonder" is the greatest song that has ever been written in the past twenty-five years. I am of that opinion myself...Hereafter, the price of that song shall be $25 ($500 today). Do you blame me?" (From 101 More Hymn Stories).

This is reportedly the first-ever recording. Recorded ca. April 1915 and released as Edison Diamond Disc 80276-R; find here.

Halloween party, Culver Academy, Culver, Indiana, 1915

At 5 p.m. we located four tents, fires burning and, by the mercy of God, no precautions, no sentries and men lounging about. The country was good for stalking and we were well in position for a rush at dusk. We used bayonets only and I think we each got our man. Drought got three, a great effort. I rushed into the officers' tent, where I found a stout German on a camp bed. On a table was a most excellent Xmas dinner. I covered him with my rifle and shouted to him to hold his hands up. He at once groped under his pillow and I had to shoot, killing him at once...

We covered the dead with bushes and I placed sentries round the camp and sent out a patrol of three men. Drought said he was hungry, so was I, and why waste that good dinner? So we set to and had one of the best though most gruesome dinners I have ever had, including an excellent Xmas pudding. The fat German dead in bed did not disturb us in the least, nor restrain our appetites.

Diary entry of 28 December 1915 of Richard Meinertzhagen, officer in the British Expeditionary Force, fighting in German East Africa.

De Chirico, The Double Dream of Spring.

During what would be the last years of his life, Claude Debussy suffered from rectal cancer and heard Western civilization thunder to pieces not far from his Parisian home. He turned bleak, nationalist, despairing--in letters, he would disparage the works of Strauss and Schoenberg (indirectly) as "Austro-Boche microbes...spreading through art."

Still, Debussy hoped for some sort of renewal when the war finally ended, writing to Stravinsky that new beauty would be needed when the cannons ceased firing. He embarked on a sextet of sonatas for diverse, unusual instruments (e.g., the never-completed fourth was for oboe, French horn and harpsichord). He only finished three.

The second, Sonata for Flute, Viola and Harp, composed in 1915, seems to be Debussy returning to an idyllic past--in particular, to his early glories L'Apres Midi d'un Faune and Syrinx. As James McCalla wrote, both the flute and the harp have pastoral associations, with the viola "acting as a timbral meditation between the other two instruments." And the first movement, featured here, is simply entitled "pastorale."

Debussy died in March 1918, just as Paris was being shelled from the air by Gotha planes and by "Big Bertha" guns, stationed 75 miles out of town. (I recall reading somewhere that shells that hit the Seine would scatter fish over the riverside Paris streets.) Given the chaos of the period, Debussy's death was ignored, his funeral almost a secret--Walter Morse Rummel wrote that you could have counted on your fingers the number of mourners at the cemetery gates. A while later, some French critics wrote in the newspapers that Debussy's death was something of a national sacrifice.

Performed by Ernestine Stoop (h), Eleonore Parmejier (f) and Prunella Pacey (v); on Debussy's Harp Works.

Next: Threads (bang bang, shoot shoot)

No comments:

Post a Comment